Opinion | Scientism in political discourse about Algerian space science

The Algerian Prime Minister recently boasted about how the Algerian flag now flies high along side 14 of the biggest nations in the world. His declaration was almost ceremonial, Algerian experts, he asserts, are now amongst the top experts in space science, and this achievement, he continues, is “no coincidence but rather the result of the state’s strategic policy that prioritises investment in the Algerian youth”. Mr. Mebarki, the minister of higher education and scientific research, has also made similar declarations.

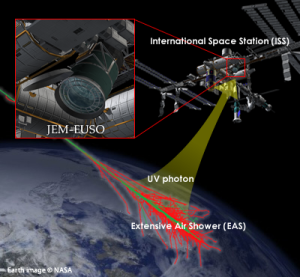

The great achievement in space science that our politicians are referring to is a technology and knowledge transfer project headed by the Centre for Advanced Technological Development (CDTA) as part of JEM-EUSO, which is a Japanese-led project to develop a cosmic ray observatory on board the International Space Station. The project brings together over 300 researchers from 80 institutions worldwide, 31 of which are from the universities of Annaba, Constantine, Tlemcen, M’sila and Jijel, as well as researchers from CDTA and the Centre for Research in Astrophysics and Geophysics (CRAAG).

This project is indeed a fantastic opportunity to promote scientific exchange and knowledge transfer in space science and related fields between the institutes and researchers involved. One wonders though whether this “achievement” is truly the result of a strategic and visionary state policy. Could this project be a true measure of the effectiveness of Algerian science policies, or are the politicians exploiting it to give state science policies credit where credit is not due.

Exploiting science

Over the past couple of years or so, the DGRSDT – the main government body managing research institutions and strategy – has been working on the third law for the 2014-18 national science and research strategy. The new law was scheduled to pass through the National Assembly to be voted upon last November. Prior to this, Prof. Aourag, who heads the DGRSDT, spoke to the media on various occasions about the major outlines of this new law (for example, see this interview). Additionally, the DGRSDT presented a draft of the law to various universities and research centres around the country throughout the first semester of 2013 as a form of consultations with the community of academics and researchers.

What is surprising is that neither Prof. Aourag’s interviews and media statements nor documents made public by the DGRSDT or its affiliated bodies contained much reference to space science, basic research in astronomy or astrophysics, nor anything about the specific involvement of our universities and research centres in the JEM-EUSO project. It is difficult to attribute this involvement to a visionary state policy when space related sciences seem to take such a peripheral place within the previous and new laws for national science and research strategy. Just where else are plans for space sciences supposed to be fully articulated otherwise?

Also surprising is the fact that a recent external review of CRAAG’s activities and plans that was supposed to cover the next 5 to 10 years did not include a review of their involvement in the JEM-EUSO project. According to researchers involved in the review process, the subject simply did not come up during the discussions. Why would CRAAG leave such an important project off the review table is a question I won’t attempt to address. But this reinforces the assumption that state strategic policy had not much to do with this particular development.

One important goal of scientific research should be to advance socio-economic development, something that Algeria is in much need of. State policies and resources should be devoted to support this goal. Space science in particular is one field where the impact of the infrastructural investments devoted to it reach far beyond the field’s immediate application areas. For example, in his interview with Inspire Magazine, Prof. Melikechi described how his involvement in the NASA Mars Curiosity Rover mission is both based on and contributes to advancements in the area of laser technology and its use for early cancer detection. Meanwhile, the status of cancer treatment in Algeria is not to be envied. Dr. Ernst Stuhlinger, associate director of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Centre in the 70s, gave a more thorough explanation -and justification for- the seemingly extravagant government spending on space science and its far reaching impact in this inspiring letter.

The blatant reality is, just like the majority of Arab and Muslim as well as African countries, Algeria is still really far behind when it comes to space science. One therefore imagines that a visionary and strategic state policy designed to boost this important area of science would address fundamental infrastructural issues in order to build appropriate foundations that ensures the long term flourishing of Algerian space science. According to Dr. Guessoum recent analysis of the state of astrophysics in the Arab world, a revival of space related sciences should include serious investment that balances spending between applied and basic research, including investing in high quality equipment, updating university programs to reflect the state of the art in these fields, as well as establishing international exchange programs and increasing expertise in the management of large scale scientific projects.

Additionally, a long term strategic vision should ensure that Algeria teams up with regional players who are also in the process of building a foundation for space related sciences. It should endeavour to develop robust space policies and programs in order to strengthen the relationship between the activities of its space agency and national development plans, while also effectively contributing to the establishment of the African Space Agency.

A strategic state policy that prioritises investing in the Algerian youth should also address the dire status of the educational system (primary, middle and high school). In particular, educational programs should be updated to adequately incorporate STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and maths) if they are to instil future generations with critical thinking and problem solving skills, which is the best way to truly promote a culture of science in the country. Just how much of the Algerian national budget is devoted to space science? What is the place of basic research in the new national law for science and research? How much development is going into Algerian universities -beyond buildings that is – or the educational system for that matter? And what is the situation of the Algerian student, researcher and academic in comparison to those other nations who, according to the prime minister’s declarations, we are now supposedly in their league? Unfortunately, the bill doesn’t look too good, and no amount of ceremonial declarations can hide the blatant facts on the ground.

Scientism & the myth of the written (scientific) word

The way contemporary political discourses exploit science bears a striking resemblance to an old phenomenon, one that was vividly articulated in an intriguing passage of Malek Bennabi‘s autobiography. A major part of Bennabi’s work was concerned with dissecting the impact of ideas on societies and their contribution to the birth, progress and regress of civilisation. In this particular passage, Bennabi writes about the emergence of new ideas that followed an unprecedented boost of intellectual activities during the 1920s and reflects on how these new ideas changed the dynamics of culture and intellect in Algerian society:

هذه الأفكار [الجديدة] المتداولة في الشارع كانت كمنشار يقوم بعملية تقسيم غامض لطبقات هذا الوسط ، و قد كان قبل منسجما موحدا في الجزائر. كان هذا التقسيم يحدث في الأشخاص و الأفكار مرة واحدة . فكثير من المعتقدات الباطلة و الأوهام التي تعبر عن جهل بالعالم بدأت تحتضر . فالجهل عادة يحمل احتراما وثنيا لك ماهو مكتوب . و الجزائر بقابليتها للاستعمار و بالاستعمار كان لديها اعتقاد بخرافة الورقة المكتوبة ، فقيمتها السحرية لا تمارسها فقط في النساء العجائز اللواتي يضعن لأطفالهن (حروزا) يقينهم بها من العين الشريرة ، بل إنها تمارس قيمتها السحرية أيضا في ذلك الوسط الذي تكون في الزوايا الصوفية ، إذ تستعمل فيه حجة لا جواب عليها في المناقشات.

“إنه كتبي” يقولها واحد للتاكيد إذا آنس في وجه مستمعه بعض الشك ، “إنه كتبي” أي أنه في (كتاب) ، يقولها و هكذا يسقط الشك و تنحني الرؤوس أمام الحجة الدامغة . لقد فقد الفكر النقاد الذي توقف بتلك الكلمة السحرية كل حقل . وقد ظل متوقفا بهذه الطريقة خلال أجيال . أما الآن فقد بدأ (الكتبي) يفقد سلطانه الساحر في العقول ، و يفقد شيأ فشيأ أنصاره.

” [..] These [new] ideas have now become common on the streets and were like a saw partitioning the layers of this environment, which were once harmonious in Algeria. This partitioning was taking place at the level of individuals and ideas at the same time. Most unfounded beliefs and illusions that manifest themselves as an ignorance of the state of the world are now agonising. Ignorance usually holds an idolising respect for the written word. And Algeria, with its colonisability and colonialism believed in the myth of the written word. Its magical value wasn’t only used by those elderly women who would put Huruz [a written equivalent of an amulet or a talisman] to protect their children from the evil eye, but it was also practiced within that environment which emerged within sufi zawayas [lodges], where it is also used as an irrefutable argument during debates.

“It’s kutuby [it’s written]”, one would say as soon as one senses a shred of doubt in the face of their interlocutors, “it’s kutuby”, that is it’s written in a book [kitab], one would say, and just like that, doubt disappears and heads bow in the face of the irrefutable argument. Critical thinking is lost with such a magical word, and has been stagnant in this manner for many generations. Now, however, the written is starting to loose its magical grip on the minds and, little by little, it’s also loosing its proponents.” (pp 106-107, author’s translation.)

Among other things, the spread of the new ideas that managed to defeat the myth of the “kutuby” resulted from the launch and spread of a number of Arabic newspapers and cultural youth clubs around the country. At a time of living under french brutal colonialist rule that actively sought to undermine culture and identity, developments of that sort marked a critical moment in Algerian modern history. The activities that helped foster these new ideas were truly revolutionary in the sense that they provided the youth with a space for an alternative discourse that challenged the status quo of the 1920s. However, 93 years later, statements similar to those made by our politicians confirm that, rather than disappear, the observed effect of the “kutuby” or the “written word” is well and alive having morphed into a new form. Science, or rather scientism, is its new disguise.

The dogmatic endorsement of the knowledge produced by science is a global phenomenon of course, for example the phrase “this is scientifically proven” is nowadays often used as if it were an irrefutable argument, impeding and shutting off debate when it should stimulate it. It is interesting how Bennabi attributes the idolisation of the “written word” that he observed in the 1920s to “an ignorance of the state of the world”. A discourse based on scientism thrives on an ignorance of the state of the world too. In this case it’s an ignorance of what science is and what its underlying philosophy is. It thrives on an ignorance of what makes a scientific argument scientific, of the nature of scientific evidence, the extent of its validity and how it is to be applied and evaluated.

Our politicians seem to exploit a variant of this kind of discourse as an attempt to shut off any criticism or dissent. All kinds of alarms should be going off when ideas tainted with scientism – which are more dangerous than the ideas of the 1920s “kutuby” – are no longer enforced by a brutal colonialist regime but promoted by official statesmen determined to convince the population that “their” strategic state policy has managed to place the country at the peak of scientific achievement, when in fact it did not.

Moving beyond scientism and into the realm of science-based ideas that shake up a nation into prosperity requires the founding of a scientific culture that promotes critical thinking and exchange rather than smothers them, it requires real investment in the Algerian youth’s education, from schools and colleges, to universities and beyond. To quote the french poet Antoine de Saint Exupéry “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.” In this spirit, a strategic, visionary and, dare I say, revolutionary science state policy that invests in the Algerian youth should at least not obstruct their longing for the wonders of the universe and thirst for knowledge, and foster an environment that helps them appreciate and instrumentalise both.

About the Author